Why (I) Write. Part 4. Poetry.

This is Part 4 of a short series reflecting on why I write.

The destroyer of worlds speaks with one thousand mouths.

—From “Tears wet the sea colour sky” (unpublished poem)

Poetry. What does it mean to me? What do I mean to it?

I suppose my love for words was embedded in me at an early age by my mother reading to me. I can remember siting beside her as she read the poetry of the Dr. Seuss books: One fish, two fish, red fish, blue fish. Simple words for a child’s mind.

In Catholic grade school we had to memorize poems in order to stand up in class at our desks to recite them. I remember a poem about a titmouse. I remember the poem “Eldorado” by Edgar Allan Poe. This must’ve been fourth or fifth grade. If memory serves I drew a spooky image of a wraith pointing the way for the knight to follow to find the lost city of gold.

But there was no city to find. It was a mythical lifelong quest.

I suppose that’s what I enjoy about writing: the quest. The endless search to find words and more words and new words and new ways of expression.

I played with poetry through high school, as many students do, in notebooks along with drawings. Experimentation. Finding your voice. Sensing what might work.

In college, because I was an English studies major, there were the requisite courses in Introduction to American Literature (Walt Whitman) and Introduction to British Literature (D.H. Lawrence). It was the early 1980s, and like any good undergraduate English major I had my love affair with Charles Bukowski, too. That went on for a while until I came to realize the inadequacies and infantilism of his work. My own poetry developed around this time and so was influenced by the “little press poets” (like Bukowski) who wrote poetry by basically writing sentences and then breaking them across lines.

A turning point in my life and writing came when I met the Lord, and I became His. I felt an instant freedom and constriction I’d never felt before. From that point forward, how I viewed the world (and words) changed. I felt and thought I had to find a new language to describe a new life and all I saw in it.

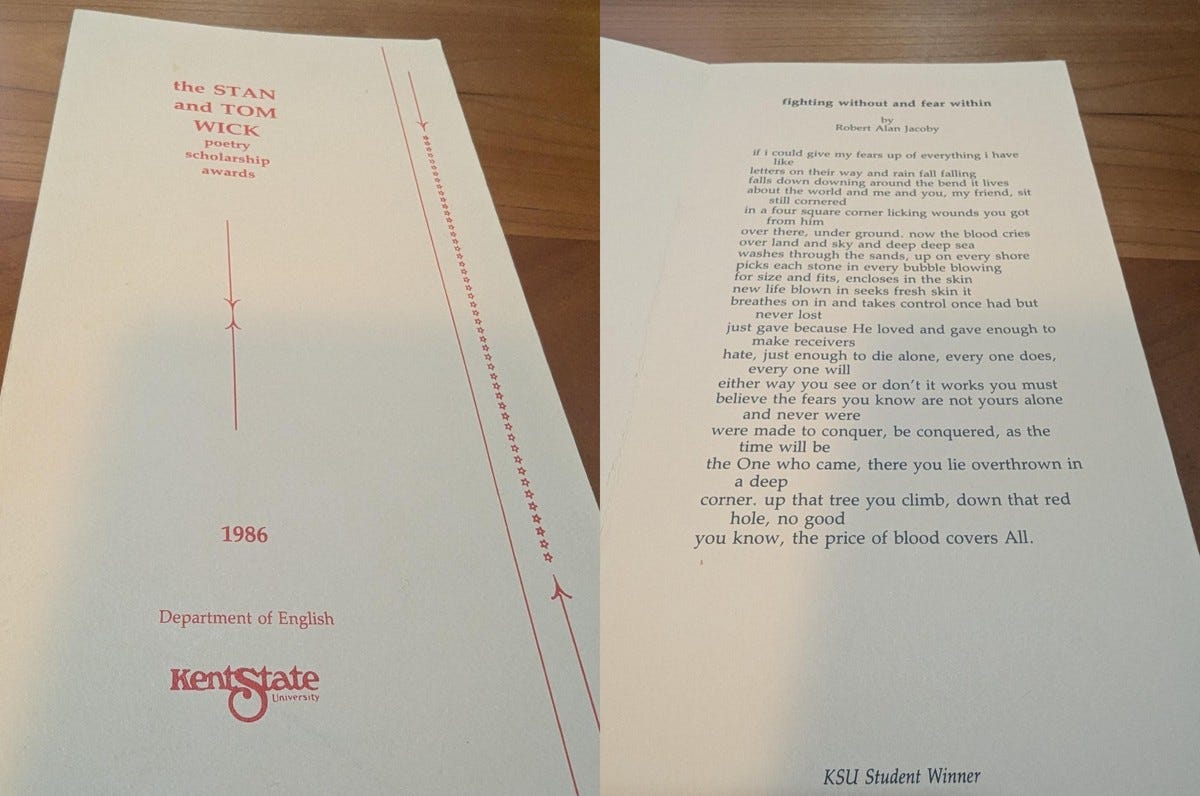

When I won a poetry award I felt validated. I’m a poet, I thought to myself. I really can do this.

But my voice for poetry went dark after this. I have a hard time bouncing around from one genre to another; I think at this time I must’ve been focused on writing short stories for my entry into creative writing MFA programs.

Around 2007-2008 I was toying with poetry again. I’d left a suffocating marriage a few years earlier, completed my first novel (There Are Reasons Noah Packed No Clothes), and was looking for new forms of self-expression to explore. I can’t recall now when or where or how I first read Dylan Thomas—I wish I could—but reading him changed my trajectory as a writer. Here, finally, I thought, was a man who wrote to that old maxim: “In a novel, every paragraph matters. In a short story, every sentence matters. In a poem, every word matters.”

In Dylan Thomas I found a kindred spirit, a man who squeezed the juice not out of every line but every word, even every syllable. In his best work I saw a purpose—a scaffolding—that I’d never seen anyone do, even attempt to do, with words.

It was the absolute compression of thought formed from English, yes, but transformed into a new language on the page. This was what astounded. Still does.

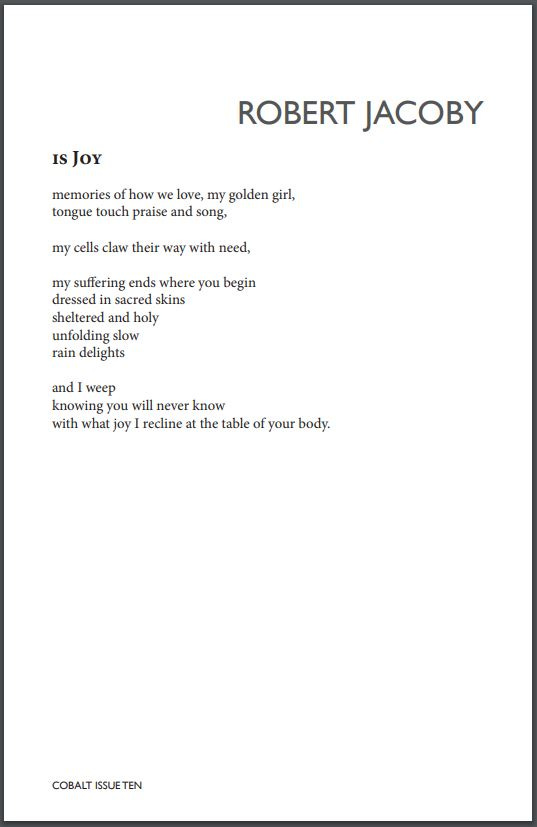

Starting in 2008 I had a run of about 5 years of explosive poetry output. I wrote dozens and dozens and dozens of poems, and more than 20 of them were published in literary magazines during this time.

The first was “The End of the Lexicon,” published in The Vocabula Review, October 2008.

The End of the Lexicon

A word can just paralyze.

Chronic words, neat completers.

Experience distills meaning.

Experiences mother meanings.

My father is dust.

Fresh.We recite braille to the deaf

carrying tomes from a decrepit youth.Every conversation cries out for parentheticals and footnotes.

Dictionary definitions are useless

when everyone’s walking around

with a different dictionary inside,blind and shameful and lonely and

finally glad

Another in that same issue was “When you are in your moon and I am in my sun.”

When you are in your moon and I am in my sun

When you are in your moon and I am in my sun,

our many-prismed passions chained, ribbon our fleshly prisoned souls,

unreflected fetal light bends to time, succumbed,

to each we mouth a shout, listening to the vacuum sing reluctantly,

when you are in your moon, and I am in my sun.When you nibble your moon and I consume my sun,

our often-tiered hearts palpate methods to construct

labyrinthine mausoleums to our coddled gods

who genuflect on glass kneecaps to their clownish creations;

when you nibble your moon and I consume my sun.When you walk your moon and I run my sun,

time twists cruel icicles through our marrow,

our isolated bones call each to all. My flesh does not fit.

Our hallowed sighs rest on crucified stars, falling,

when you walk your moon and I run my sun.When you throw your moon and I tempt my sun,

the dark matter between us mocks and cries its need:

Rockets love best when they explode.

Her now-anonymous diamond bleeds.

When you throw your moon and I tempt my sun.When I am exiled on your vacant moon,

and you are swallowed by my swimming sun,

I ask the only-obelisk questions:

Can you ever know my marbled mind?

Will I re-touch your uni-starred soul?

Life poems and love poems. Me figuring out life, at my mid-point, and me also experiencing for the first time a love that I needed new language to describe.

It is still too much the mystery, our love

(Belize, July 2010)It is still too much the mystery,

still too much like fusing suns

coming burning and mirrored split

across the sea’s table

where we know to tread cool, melodic waves

and dare to sip to slake the thirst

that madness brings.See the jellyfish seethe beneath; I point to the canopy.

Your red toenails at the end of our bed

exhort me to my kingdom.

In poetry I find a freedom and a constriction like in no other form of written expression. A thought appears. A word or phrase comes. It’s music in your mind, and like music there’s an architecture for it. You take the pen because you must. There’s a tension and a relief as the words come from the tip of your pen to the blank of the page. I can wrestle with words for days. The beautiful joy in writing poetry is finding the words and rhythms that land. That’s the thing.

This essay is part of an ongoing reflection on writing. Earlier pieces include: